Appalachian rails: Region’s trains historically defined by passengers

- Aug 7, 2023

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 8, 2023

By Phillip J. Obermiller and Thomas E. Wagner

Migrants into what is now the Appalachian region came first on foot, in canoes, and on horses and donkeys. By the early 1800s flatboats, keelboats, and eventually steamboats were added to the mix. Most antebellum African American migrants from the region walked along the Underground Railroad in a fashion similar to the many Native Americans coerced onto the Trail of Tears.

As early trails were improved into primitive roads, wagons and carriages came into use, but it was the advent of rail transportation that revolutionized travel into, out of, and within the mountains. Many European immigrants, for instance, came into the region using one-way rail tickets provided by East coast labor brokers under contract with coal and timber companies to recruit workers.

Pictures of trains pulling endless hoppers of coal are a standard part of the iconography of Appalachia. Sometimes interspersed with coal tipples or flatcars hauling logs, these images are widely used to symbolize both the region’s railroad traffic as well as the region itself. Natural resource extraction was the principal reason most rail lines were carved through the mountains, but when it comes to trains in Appalachia, passengers are frequently overlooked.

In fact, most railroads in the region offered passenger trains as well as “mixed trains” that provided both passenger and freight service, usually on branch lines. Because they ran in less populous rural areas, mixed trains rarely had more than one passenger car, and sometimes that was often a single passenger, mail and baggage car, known as a “combine.” Silent testimony to the multiuse aspect of railroading is found in the surviving depots in small-town Appalachia that have a passenger side and a freight side separated by an office for a station agent who sold tickets, managed freight, and maintained telegraphic communication along the line.

Meeting at the station

Over time, train stations became social centers, where mail, parcels, and passengers were picked up or dropped off. Some stations evolved into general stores that included a postal window. These were also the places where dreaded telegrams arrived from the U.S. War Department notifying families of soldiers wounded, missing, or killed during wartime. Before migrating north with her husband, Mrs. Anne Gentry described the local depot as a central gathering place in Green Cove, Virginia. “Everybody came and visited,” Gentry said in the book, America’s Last Steam Railroad: Steam Steel & Stars, published in 1987. “We sat out on the freight landing in the summertime and inside around the stove in the winter.”

Examples of passenger service abound. The Western North Carolina Railroad, for instance, extended a line from Asheville to Murphy in 1892. One commentator noted that passenger business was so good by the turn of the 20th century that six passenger trains ran every day between Asheville and Lake Junaluska and four daily between Asheville and Murphy. Scheduled passenger service on the line lasted until 1948.

In the early 1900s when Kenova, West Virginia, became a nexus for the Chesapeake & Ohio, Baltimore & Ohio, and Norfolk & Western railroads, author and railroad historian Tim Hensley notes some 30 passenger trains a day originated or terminated at the city’s Union Station.

An unfortunate indicator of the density of passenger traffic in the mountains occurred in 1904 when two trains of the Southern Railway collided near New Market, Tennessee, killing 56 and injuring some 106 passengers.

There were many popular trains carrying local people through Appalachia including the “Tweetsie” (named for the sound of its whistle echoing in the mountains) which began running between Johnson City, Tennessee and Boone, North Carolina in 1919. The 277-mile Clinchfield railroad ran through Kingsport, Tennessee, where the tradition of a holiday “Santa Train” started in 1943. Today the Santa Claus Special travels from Kingsport to Pikeville, Kentucky, stopping to deliver gifts along the way before bringing Santa back to Kingsport for the annual Christmas parade. The Special was a part of the regularly scheduled passenger service on that line until the service was discontinued in 1955.

Railroaded: Unjustly convicted

Some Appalachians were not voluntary passengers. A race riot that began in Corbin, Kentucky, after a stabbing in 1919 resulted in some 200 Black residents being forced into railcars bound for Knoxville. In Southern Appalachia, enslaved Blacks laid track and helped build tunnels and trestles prior to the Civil War. Post-war chain gangs made up of falsely arrested Black prisoners continued to build railroads in the region. In one instance 19 African Americans shackled to each other on a workboat drowned when it overturned on the Tuckasegee River while they were being ferried across to dig the Cowee Tunnel for the Western Carolina Railroad. The legendary John Henry is thought to have been one of the convict laborers digging the C&O’s Lewis Tunnel in Virginia, where prisoners worked alongside steam drills night and day.

After the Civil War, Black migrants often came into the region on trains to do the hard work of maintaining roadbeds (“lining track”) or serving as brakemen; before the adoption of airbrakes many Black brakemen were killed or maimed doing this dangerous job.

Graphic images of early 20th century train travel often feature luxurious Pullman cars with passengers served by uniformed Black Pullman porters and maids. In southern Appalachia, where few Pullman cars were in use, Jim Crow prevailed — train cars reserved for Black passengers had no water, heat, baggage racks, or toilets, much less sleeping accommodations. The so-called Chicken Bone Express indicated the lack of food service for Black train passengers who brought along fried chicken to eat during their train journeys. Train stations in the region also discriminated by race; for instance, by 1899 segregated waiting rooms were mandatory across North Carolina. Larger depots carried segregation a step further with a separate “ladies waiting room” and a “Negro waiting room” (that included Black women) along with a freight room and a general waiting room.

During the Civil War, railroads in Appalachia carried soldiers and supplies into battle for both the Union and the Confederacy, making them prime targets for either capture or destruction. After Generals Grant and Sherman took the rail hub at Chattanooga, for example, Confederate soldiers were driven down the Western and Atlantic Railroad into Georgia, opening the way for what would become Sherman’s March to the Sea. Whenever possible, Union soldiers tore up tracks in captured territory and wrapped them around trees creating what became known as “Sherman’s neckties.” It was, however, more typical for combatants to blow up tunnels or burn trestles, thus impeding both passenger and freight traffic throughout Southern Appalachia.

Trains remained the fastest and most economic means of regional transportation well after automobiles began rolling off assembly lines in Detroit. In addition to the costs of purchasing, fueling, and maintaining a car, roads often remained primitive well after the passage of the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916. This legislation did little to improve automobile travel in the region in any meaningful way until the 1930s.

Train Migration

The United States Numbered Highway System, initiated in 1926, eventually gave rise to interstate routes such as U.S. 23 (the Dixie Highway) and U.S. 25, two early highways into and out of the mountains. Despite more and better roads, the scarcity of cars, tires, and fuel during the war years of the 1940s made bus and rail travel the principal means of transportation over long distances. Thus, given the abundance of rail passenger service and the relative ease of access to urban areas in the East and Midwest, it is reasonable to assume that people leaving the region went principally by train until the mid-20th century. In the words of historian John Alexander Williams, in his book, Appalachia: A history, “feeder railroads built outward from the trunk lines into the mountains (linked) the resources of Appalachia — including its workers along with its minerals and trees — to the factories of distant cities.”

Sidetracked: Shunted aside

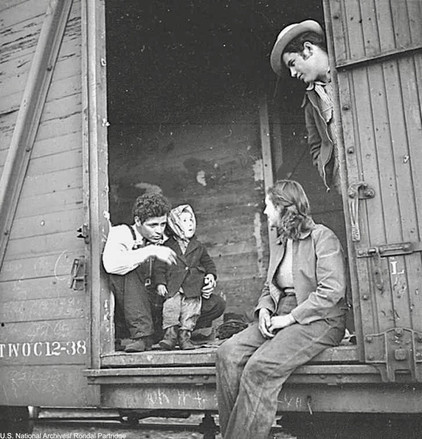

Over time, better roads, the high cost of laying new rails, and the need for flexibility led to the increased use of school buses, coal trucks, and long-distance motor coach lines in the region. By 1935 national intercity bus ridership surpassed the volume of passengers carried by the Class I railroads for the first time. During the Great Depression of the 1930s some migrant laborers and even whole families rode the rails out of the mountains.

(Left) A man is helped onto a railroad freight car during the Great Depression. (Right) A family occupies a freight car during the Great Depression. (Photos courtesy of the National Archives.)

During both World Wars, Appalachian soldiers rode trains to training camps, to visit home before serving abroad, and to return home after their military service. At the same time, many women and men from the mountains rode trains to cities in the Midwest and East to work in wartime factories and shipyards, or to join family members who had migrated earlier.

In her widely read novel, The Doll Maker, Harriette Arnow describes Kentuckian Gertie Nevel’s travel by train to join her husband Clovis who found work in Detroit. Set in the midst of World War II, the train is overcrowded. She and her children change trains in Cincinnati, introducing her to a new world: “All the hours (waiting) in Cincinnati had been in a house-like thing, big and high above…but smothery crowded down below, with people fighting for standing places in the lines before the gates,” Arnow wrote.

It was not an easy trip. “. . . as she had done for hours, she pressed her big body as far back in the seat as possible and against the window, where, in spite of two thicknesses of glass, the cold, like water trickling, seeped into her hip so that it ached from the cold. She had held Amos and Cassie, one on either knee all the way from Cincinnati to make room for Enoch and Clytie, wedged into the other half red plush seat. (Tickets were originally sold by the seat rather than by the person, so parents with children could crowd together on a single seat paying only one fare.) She looked quickly about for Reuben and found him only after what seemed a long search in the dim light. He was on the arm of the seat right in front of them but across the aisle: asleep, she thought, his head bowed on this arm along the seat back.”

Although fiction, Arnow’s description of the trip typifies the experience of thousands of Appalachians who migrated north by rail to join the post-war economy as industrial workers.

The rise of the Interstate Highway System in the 1950s marked the decline of passenger service on most railroads in Appalachia and across the nation. Amtrak, however, still maintains passenger routes through the Appalachian counties of 11 states. Freight still moves through the region as well, although in some areas train loads are more likely to be chemical than coal, as evidenced by the disastrous Norfolk Southern derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, on Feb. 3, 2023.

At the outset of the 20th century tourists rode passenger trains to visit destinations such as Natural Bridge, Kentucky, a private attraction started in 1895 by the Lexington and Eastern Railroad and later operated by the Louisville and Nashville Railroad after it acquired the landmark in 1910.

As the Appalachian economy transitions from extraction to, among other things, recreation, passenger cars filled with sightseers still ply the region’s tracks. Trains continue to carry tourists on short runs through the mountains — The Great Smoky Mountains Railroad in North Carolina, for example, or the Blue Ridge Scenic Railway in North Georgia. Today similar excursion trains are operated in the Appalachian counties of nine other states.

It is clear that trains affected life in the region in ways similar to that of the rest of the nation but, despite the popular coal-car imagery, Appalachia’s trains have always carried passengers.

The authors appreciate the encouragement and insights of the members of the Cincinnati Railroad Club, of Ross Cooper at Appalachian State University’s Belk Library which houses the Appalachian Rails and Railway Collection, and of railroad aficionado Jake Kroger. Any errors of fact, interpretation, or omission are ours, not theirs.

Phillip J. Obermiller is a senior visiting scholar in the School of Planning at the University of Cincinnati. Thomas E. Wagner is a university professor emeritus in the School of Planning at the University of Cincinnati.