Flood alters Hindman Settlement School's ‘safe bubble’ experience

- Feb 28, 2023

- 7 min read

Editor’s note: During the predawn hours of July 28, 2022, Hindman, Kentucky, experienced historic flooding causing 17 deaths in Knott County and massive damage to property and homes in and around the town, including the historic Hindman Settlement School. The flooding threatened not only the school’s campus, but also members of the Appalachian Writer’s Workshop who were staying there. This is a description of that experience from one of the writers attending the workshop.

By Amy Richardson

When I think about the Hindman Settlement School, I get the same feeling I always had going to visit my grandmother’s house growing up. I know I’ll be welcomed with hugs and hellos, a big bag of Grippo’s potato chips, an ice-cold Ale-8, and genuine interest in whatever is happening in my life. I look forward to stories and songs shared on porches, inspiration after intensive workshops, and reflective moments at the McClain Chapel beside the grave of James Still, where you can look over and see the whole town. From the first time I attended the Appalachian Writers Workshop at Hindman, I have instantly felt accepted and appreciated for exactly who I am. It’s a feeling I had been missing before arriving on July 24, 2022.

During the 45th Annual Appalachian Writers Workshop at Hindman, a storm rolled in on Wednesday, July 27. We had spent the day in workshops writing, reading, laughing, and swapping stories as usual in between spurts of small showers. We made jokes about getting wet as we passed back and forth between buildings, noted how dreary days make coffee taste better, and offered condolences to tired faces, blaming our collective exhaustion on the weather and not the fact we’d all been staying up too late.

As the day was ending — and as the flood, we would learn, was actually beginning — we spread across campus at the end of the last session, huddling on porches to continue conversations late into the night as the storm picked up.

None of us knew what would happen in the wee hours of morning. Many of us went to bed a little after midnight, listening to thunder and watching lightning flash through the curtains as we dozed. At about 2:30 a.m., we woke to knocks on our doors as Josh Mullins, the program director, alerted us to a power outage and rising water. Some vehicles were in danger of being swallowed by Troublesome Creek, and by the time we made it to the parking area, several cars had already been overtaken by the flood.

Around the same time, writers housed in the Great Hall, near where those cars were parked, needed to evacuate. As the water visibly rose behind us we rushed to move people and their belongings uphill to safety with those of us staying in Stucky, a building on the hillside overlooking the Great Hall and Troublesome Creek. I felt honored to assist author George Ella Lyon with moving her stuff. Even as it was happening, I had a weird sense of irony about the way I was finally brave enough to talk to her because our lives were in danger. I remember looking back toward the offices and seeing flashlights where Josh Mullins and Sarah Kate Morgan were working to grab what important things they could before the doors collapsed from the current, water moving from their ankles up to their chests.

Once we had them moved and settled, the rising water was threatening more cars. We made the call to move them to the only place they could go — lined bumper to bumper along the skinny driveway in front of Stucky. Since I have vision issues that make driving in dark rain difficult under common conditions, Caleb Johnson moved my car for me. In rapid succession, all of our remaining vehicles were positioned below the porch, where we took turns looking out at the flood.

Watching through pitch black, we could see only during increments of lightning flashes how high the water was. Once we had done everything we could physically do to ensure our safety, and to ensure that we would have transportation when the water receded, all we could do was wait.

The hours were long and uncertain. I paced from the living room — where people sat sharing methods for reducing anxiety and remaining calm — to the porch, where the crowd seemed focused on our ultimate doom. It was difficult to know where I fit.

I wanted to feel calm. I wanted to feel anything other than the gut-wrenching panic making its way up my throat as I thought about my kids and hoped to hug them later. I was as terrified as the energy on the porch and kept imagining disastrous scenarios, such as the water rising all the way up to where we were waiting. Or more likely, a mudslide right into our refuge, taking us out with the trees and rocks from the hill we were perched upon and sending us right into the increasing flow of Troublesome.

In some ways, I felt numb, like I was in an unimaginable nightmare that I couldn’t wake from, jarred completely out of the happy, safe bubble I had always felt I existed in at Hindman. But I knew I wasn’t asleep. I took comfort in Nicole’s sweet and aptly named dog, Solace, who worked so hard to offer us all some consolation amid our alarm.

When Sarah Kate came in with Preston, her kitty, and her dulcimer, I jumped up in relief to see her. My last glimpse had been while she was saving computers and important items from the office, which was submerged by then. She and a few others living in the apartments sheltered with us in Stucky as the risk of mudslide was more imminent at the apartments.

I sat beside Sarah Kate on the couch wrapped in blankets, existing in stretched out time, holding Preston until he became too squirmy for me, staring up at the skylight and watching the sky brighten from black to hazy gray. We all waited for our first real look at the damage in daylight.

We walked outside in shocked bunches. Some wandered downhill toward the Great Hall, some toward town. I walked toward Mr. Still’s grave and the chapel, where I always found peace during previous visits. I waded in cold water running over my feet for the length of the path. I noticed water running down the hillside carving new paths in other places. Perhaps the flood wasn’t finished. Before I made it all the way to the chapel, I looked up and saw town. I thought to snap a picture, a horrifying scene of places I love submerged. My mind hadn’t yet ventured to the people.

From left to right on July 28, 2022, the path toward Mr. Still’s grave and Hindman’s flooded Main Street; Looking at the iconic bridge, of which only the railings were visible after daylight that morning; Looking toward the Mullins Center with the Stucky building in the background.

I walked down the hill to join some others walking into town. We watched swimming pools, gas cans, lawn chairs, and kayaks wash downstream. We stopped at the giant blue horse mailbox to stare at water running down Main Street, over the intersection with Highway 160 where we turn while driving in. We could see the busted-out windows of the Artisan Center. As we stood in shock, others were walking downtown, too. People who live there. Community members.

We talked to a lady who came down to search for her friend’s grandmother. She said her friend was afraid to look, afraid she’d find her body. They identified her trailer from the living room carpet in broken pieces on the guardrail and her late son’s quilt that had hung from her bedroom door. Another lady told us she was 60 years old, had lived there her whole life and had never seen anything like this.

When we returned to campus, a friend had just spoken with a sheriff’s deputy who had broken down in tears telling about watching a trailer carried away by flood waters with a family trapped inside and standing in the door. The deputy couldn’t reach them. So many heartbreaking stories were emerging with the dawn.

We knew that as soon as the roads were clear the best thing we could do in the moment was to get out of the way. So, we quickly packed up, organized carpools for those whose vehicles were taken by the flood, lined up in a caravan and started out on our separate ways.

As much as coming into Hindman had felt like coming home, leaving amid a disaster felt like abandoning family in a time of great need, even if it was the best thing we could do right then. I know we are all working in ways we can from afar to send help and support. I have made the drive back to take what I could and to help with the immediacy of rescuing the archives. But I still feel a hole ripped right through me thinking about all of the unmet needs and those who suffered so much loss. I know that many others do, too.

Remember the urgency of those wee morning hours. The people who felt that terror in their own homes and who weren’t fortunate enough to flee. I have already witnessed so much compassion rising as those flood waters did. Let us hope it doesn’t recede as quickly.

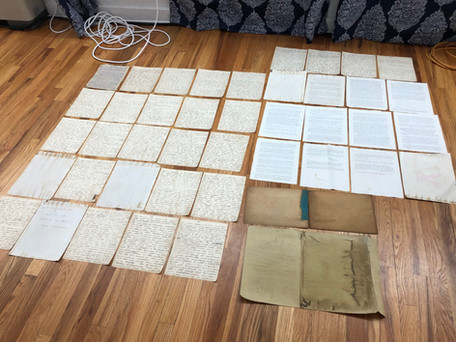

Since I’ve been back home the feeling of restlessness, the urge to do something has been uncontrollable, rising up through me when a news story about the flood is on, and when I scroll social media and see updated numbers of dead and displaced. I was able to drive back down and help sort out some of the mess the flood created in the archives at Hindman — pulling pictures, letters, dolls, and swollen papers from inches of foul-smelling mud. Helping out settled that restless feeling for a few hours, but then it surged right back as soon as I awoke at home the next morning. I can’t sleep. I can’t focus. I feel driven to read constant updates and feel guilty because I was able to come back to an untouched home, a whole family.

From left to right on July 30, 2022, pages from a journal in the archives are laid out to dry in the Mullins Center; Boxes are assembled beside the Mullins Center door leading to the archives, where people worked to save historic documents; Pictures from the archives are hung to dry inside the Mullins Center.

I am already looking forward to next year’s workshop when we can hug, share healing stories, and reconcile our abrupt departure. When I can walk that path to the chapel, pay my respects to Mr. Still and look out on that mending community.

Amy Richardson is a farmer, writer and visual artist who is passionate about environmental issues. Her work has appeared in Black Moon Magazine, Pine Mountain Sand & Gravel, and is forthcoming in The Yearling. She works on her family farm in Carter County, Kentucky.